The Guardian yesterday announced details of its new membership programme.

As a milestone in the evolution of newsbrands it is an intriguing move.

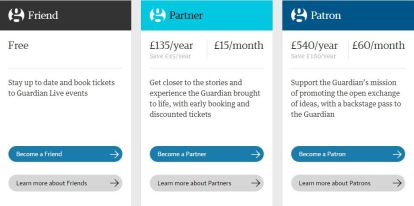

Other newspapers already have membership schemes, but they are generally built around a paywall model in which subscribers pay for access to editorial content, with a few extras goodies such as competitions and ticket offers thrown in for good measure.

The Guardian on the other hand has placed a large bet on its ability to build a sustainable revenue model based on its readers’ willingness to pay for a) access to exclusive live events and b) patronage of its journalistic ethos.

The question is whether the bet will pay off, and in doing so potentially also pave the way for other newsbrands to build profitability without building paywalls in a digital future.

Clearly, the Guardian was never going to introduce a paywall.

Its commitment to open journalism has helped it build a huge online following, with over 100m browsers worldwide.

This makes the Guardian the third largest English language newsbrand in the world (behind the New York Times and Mail Online), despite selling fewer than 178,000 print copies each day in the UK.

The problem Guardian management faced was how to translate this influence into revenue, without abandoning their principles or alienating their readership.

To my mind they have come up with an elegant solution, which has the potential to deliver on all fronts.

They have created a free product, which will allow them to gain a better understanding of a large proportion of those 100m online browsers, with all the attendant benefits this will bring to their CRM and ad sales programmes.

And they have created paid products which will generate income whilst simultaneously allowing their most loyal followers to build a closer connection to the brand.

Those closer connections will be forged primarily through Guardian Live, a series of live events covering a wide array of topics, to which members will get priority access to tickets.

The centrepiece will be Guardian Space – a dedicated events space housed in a huge converted goods warehouse opposite the Guardian’s offices in Kings Cross.

Both the location of Guardian Space and the initial list of events give the impression of this being a very London-centric affair, but if Ken Doctor’s analysis for the Nieman Journalism Lab is correct this is just the tip of the iceberg, with “hundreds of events each week across Britain” the ultimate aim.

If true, the huge scale of the ambition is admirable.

For me it’s not just the events strand that is interesting though.

I like the overall manner in which Guardian Membership is being pitched, and how far it differs in tone from other newspapers’ loyalty schemes.

The language employed is striking – friend, partner, patron.

You are not being asked to merely subscribe, to take part in a cold financial transaction. You are being invited to join an exclusive club; to contribute your cash, ideas and energy towards the cause of progressive liberal journalism.

This is an important point.

In its excellent summary, The Media Briefing quite rightly points out that on the face of it the membership options don’t seem to represent great value for money.

But this isn’t being pitched at the rational consumer. The whole idea of patronage brings to mind somebody who is happy to subsidise the arts, either because they believe in a particular cause or for the personal kudos that comes with it.

Will people be prepared to pay £15 or even £60 a year for the privilege of becoming a “card-carrying Guardian reader”?

Many will scoff at the suggestion but initial signs are that some people will, as shown by (comedy writer & director) Graham Linehan’s tweet yesterday:

With an existing universe of 100m people to talk to, the Guardian only needs a small percentage of them to convert to paid membership before the sums start to add up.

I believe many of its readers may well look upon a Guardian readership as they do a trip to a museum. It’s free to enter and have a look around, but you also feel morally obliged to contribute something to its upkeep.

It’s interesting to note that despite the economy enduring a long period of recession, the amount of money raised by UK cultural institutions over the last 5 years through donations, sponsorship and memberships has continued to increase, reaching a total of £293m last year according to DCMS (see Figure 3 here).

So whilst it’s a different category and context, there is a precedent for people to put their hands in their pocket to support institutions they perceive to be culturally valuable.

If the Guardian can position itself in that same bracket with enough of its readership it will be well on the way to success.

What do you think? Will this approach work?

Will enough people sign up as partners, patrons or event attendees to generate sufficient income?

Or is the battle for paid online content already lost, and will Guardian Space ultimately be viewed as an expensive folly?

I do hope not.

For my part I applaud the Guardian’s innovative thinking and the boldness of the execution.

I wish them the very best of luck with it.